Mike Waller and the Era of Tough-Guy Journalism

Mike Waller wore brass knuckles when he committed journalism.

He was the top boss when I worked at the Kansas City Star in the 1980s. We should have called him Mikey, like those other toughs from the hood, guys like Frankie and Vinnie.

At 5-foot-8, he was a diminutive character who could sneer at you with a face-full of attitude. Like all hooligans, he finished sentences with a “yeah.”

Waller’s kind are now extinct in an era when newspapers are run by hedge-fund robots. His generation had an unvarnished, blue-collar soul. They were newsroom drill sergeants who roughly guided untested kids like me through their journalistic basic training.

When Waller called the shots, the oldest veterans might have served in World War Two. Back then, it was an ink-stained trade. The Star had once hired a guy fresh out of Leavenworth prison as their police reporter because, as an ex-con, he got coppers.

Waller had that same common sense, and I was proud to work for him. There was no bullshit mean-spiritedness to the man, even though he wore his swagger like a pair of thousand-dollar shoes.

In those days, the old guard could be downright mean-spirited. A 24-year-old reporter once asked to send writing sample to one veteran editor.

“Don’t bother,” he snapped. “Nobody writes anything until they’re 30, anyway.”

A friend who in the 1960s worked for the old Chicago News Service told of filing his first deadline story, and then asking the night editor what he thought. “I ought to shove that story down your throat, pull it out your ass and throw it in your face,” he said. “If you can call that a face.”

Not Mike Waller; he was one tough guy with a sense of humor.

I arrived in Kansas City from Norfolk, Va., a kid who thought he could turn a phrase.

My predecessor on the KC police beat, a beast of a reporter named Paul Hutchinson, had landed so many investigative hits on the KC cops that editors feared for his safety.

The Star needed someone less threatening, and I was virtually harmless.

I didn’t see too much of Waller. As the cops reporter, I was at the lowest rung on the ladder of newsroom hierarchy, while he sat at the very top, presiding over both the afternoon Star and the morning Times, which were crammed into the same ancient, charmless newsroom.

He’d started his career in 1961 as a clerk in the sports department of the Decatur Herald in Illinois, before moving up to reporter and editor. He worked as a reporter for the Cleveland Plain Dealer and was an executive editor at the Louisville Courier-Journal.

Now he called the shots in my life. But were lots of people between us, good journalists forged from Midwestern stock. Like the Star’s editor, Dave Zeeck, a strapping Texan with a broad face and an easy demeanor.

And the eccentric-but-likable city editor, Darryl Levings, who was known to put his finger in your face, the so-called Levings stab, to make a point. And Steve Paul, a bohemian desk editor who was into jazz and Ernest Hemingway.

They’d all been though the crucible together. In 1982, the Star and Times had shared the Pulitzer Prize for their coverage of the infamous collapse of the skywalks inside Kansas City’s feted Crown Center Hotel, a disaster that killed 114 people and injured another 200.

The Star wrote 300 followup stories that presented damning proof of design and construction flaws. Kansas City’s cultural elite insisted the newspaper was damaging their reputation, and began campaigning editors to back off.

Fat chance of that. Rumor said the publisher, Jim Hale, had thrown a drink in some socialite’s face when he ran down the papers’ good name.

For a kid like me, just 25, the Star was the real deal, a fish tank full of dangerous journalists who turned piranha at the scent of a good story.

And Waller was their tough-guy leader.

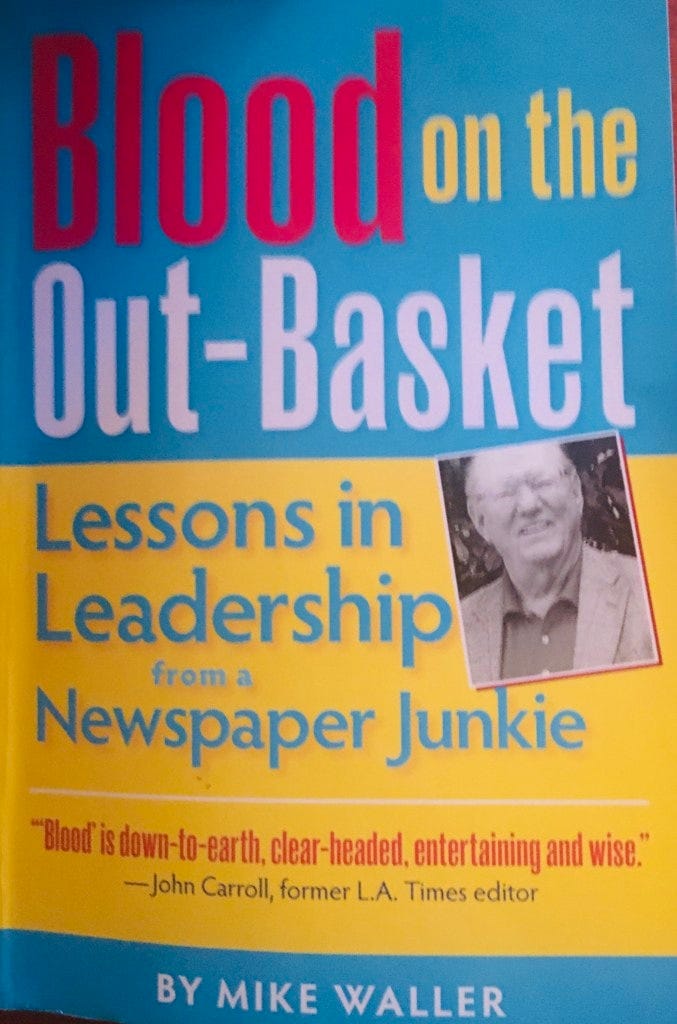

The man had a sense of humor. Years later, he would write an editor’s guide called Blood on the Out-Basket, named for the day a Star editor named Grace jumped in horror at the sight of blood on her desk.

“That’s the name of my book!” Waller shouted.

The Star taught me how to become a better reporter and I eventually broke stories on my beat. One Friday afternoon, I sat in Waller’s office as he reviewed the art for a piece that was leading the Sunday paper.

He hated it. Suddenly, he started making puking noises, as if the photos actually sickened him. This continued.

Then Waller paused and looked at me.

And then he winked.

The story was one for the boys over beers that weekend.

Not long afterward, I was in the newsroom when Waller sauntered past. He was wearing a piece of masking tape over the bridge of his broken glasses.

I told him that any kid in my neighborhood would get his ass kicked for wearing a pair of glasses like that.

Suddenly, Waller was leaning in close, teeth clenched, like I was some harmless puppy who’d just taken a bite out of him, which I had.

“Yeah, Glionna,” he said. “See that sign over there by [Times managing editor Monroe Dodd’s] office? It reads MAS. Do you know what that stands for? It stands for morning asshole. And see that sign in front of Dave Zeke’s office? It says AAS. And it stands for afternoon asshole, yeah.”

I looked down and, without thinking, responded.

“Well, Mike,” I said. “I guess that makes you the all-day asshole.”

My career flashed before my eyes. Sweet Jesus, what had I done?

Waller looked up with a wise-guy smile.

“I like that” he said, “the all-day asshole.”

Then he spun on his heels and walked back toward his office.

After 35 years, I had the urge to call Waller, so I telephoned Dave Zeeck up Washington State for his number.

He said Waller hadn’t changed. After leaving the Star in 1986, he became editor of theHartford Courant, before moving on to become the publisher of the Baltimore Sun.

Now he was near 80 and retired. He still couldn’t figure out Zoom meetings and had held on to his AOL email account, dinosaur that he was.

Waller picked up the phone at his home in Hilton Head, S.C., where he’d lived since retiring in 2002. He didn’t remember me specifically, not that I’d expected him to.

But he did recall those battles with the Kansas City civic set after those Hyatt stories, how they even made a pilgrimage to the newspaper’s corporate owners in New York to get them all fired.

I asked him about his style.

He said newsrooms become paralyzed if people are afraid of making mistakes, which happens with too much corporate mentality.

“I was all about staying loose, keeping people loose,” he said. “The more freedom they had, the looser they got. And then they did better work.

He laughed about the puking and all-day asshole stories.

“See what I mean?” he said.

He talked about his golf game, how he’d played 4,700 rounds before arthritis wracked his hips and shoulders.

I wished him well on the links and then we hung up.

Later, I regretted not telling him two things. One, that he was the most bad-ass newspaper editor I’d ever worked for.

Two, that he didn’t really look all that bad in those taped-up glasses.

In fact, he looked like what he was, a tough guy.